For two decades now, Germany has been steadily aiming for a shift in economic paradigms, moving towards an energy sector that is sustainable both environmentally and technologically. Poland in turn is developing its energy supply in an ever starker opposition to Germany, petrifying the existing, growingly outdated model typical for the 19th century, based on a “central coal plant” or its nuclear substitute. The latter is a model of energy policy that was state of the art in mid-20th century. This situation introduces a growing dissonance in the generally good neighborly relations between the two counties.

Poland’s opposition to the German energy policy has been increasing since 2008, when after the political green light for the “3×20” Climate Package, the EU was shaping the directives on the emissions trading scheme, “clean coal” technology, renewables and the means of achieving energy efficiency targets. At that time, the German government was already implementing its 2006 strategy, according to which by 2022 all nuclear plants were to be phased out and substituted – even outgrown – by renewable energy sources (RES). In the difficult negotiation process of late 2008, over the final shape of the energy and climate directives, Poland was looking for support not to its Western neighbor, but to the new member states and to France, which empowered the coal power sector and became an impulse for the rash decision to begin such nuclear programs. It also meant that despite the strong EU support for RES the implementation of the renewables directive ended up at the far end of the Polish government’s priority list. That mode of thinking was then in 2009 inscribed into the official strategic paper “Poland’s energy policy until 2030”, sealing the programmatic divergences between Poland and Germany.

Romantic Germans, pragmatic Poles?

The Fukushima meltdown confirmed the direction of Germany’s energy policy, and deepened the divergences. The final decision of the German ruling coalition on the complete phase out of nuclear energy before 2023 was presented in Poland as the effect of an irrational emotional surge after the tsunami, due to which “the greens pushed the (romantic?) Germans against nuclear energy” (as for example Konrad Szymański, MEP, would have it). Ironically, the air of pragmatism is in these circumstances continuously given to the statements of the national energy companies, that although the German breakthrough is an idea detached from economic realities, it is beneficial for Poland because… it paves the way for the export of electricity from Polish coal plants to Germany.

Nobody wants to see that what is happening is exactly the opposite – Germany has a surplus of energy that it is exporting. Along with a number of other EU member states (e.g. Great Britain), implementing the Climate Package boasts a wide investment program in the RES sector. There are 25-30 GW of new capacity being installed across the EU annually, and a great majority of that capacity is the RES. The price of energy from renewables is becoming lower than that from fossil fuels, and that process can neither be stopped nor reversed. Meanwhile, the opportunistic approach to the Climate Package in Poland has resulted in the lack of any significant new capacity development, not even for substituting the old coal plants. Poland will face an energy deficit already in 2015-2016. Unfortunately, the programmatic skepticism towards the Energiewende, including the underestimation of the nation’s potential in renewable energy will lead to the need for importing energy from, among others, Germany, and this can feed a wave of new “conspiracy theories” and irrational decisions on future energy policy.

Energy lobby in place of the state

Not noticing and downplaying the role of RES, or even blocking their development, the example of which is the nearly three-year-long delay in the implementation of the EU directive, maintains an “open door” for nuclear energy and unverified solutions in the energy sector, such as shale gas or CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage). In the face of these mechanisms, the situation is difficult for the so-called independent green energy producers as well as for foreign energy sector investors, who are operating in a very different reality outside of Poland. The Polish utilities, without a clear signal for change on the part of the government, are not making up the technological and structural distance vis-à-vis the EU.

On the other hand, in the apparent lack of other major market players, the national energy companies are becoming the key recipient of energy policy, the illusionary depositaries of the nation’s energy security. Influential lobbies, linked to the energy companies, blend with the public administration. Steering the course of policy and regulation year after year, they keep drawing Poland away from an energy breakthroughand make even the evolutionary changes difficult. It seems that it is not the energy companies who implement the state’s energy policy, but rather conversely – the state pursues the interests of the companies.

Poland and Germany at energy crossroads

As an effect of these policy differences, the energy systems of Poland and Germany vary significantly, especially when it comes to RES. The installed capacity of renewables in Germany is almost two times larger than the entire installed capacity of the Polish energy sector, and the share of RES in the German system (over 41 percent) is almost five times that of our country’s. In spite of that, the German grid operators fully manage to balance the significant production from instable sources (such as wind and solar), while their Polish counterparts have already convinced the government of the alleged threat to energy security occurring even with such low shares of wind and solar energy.

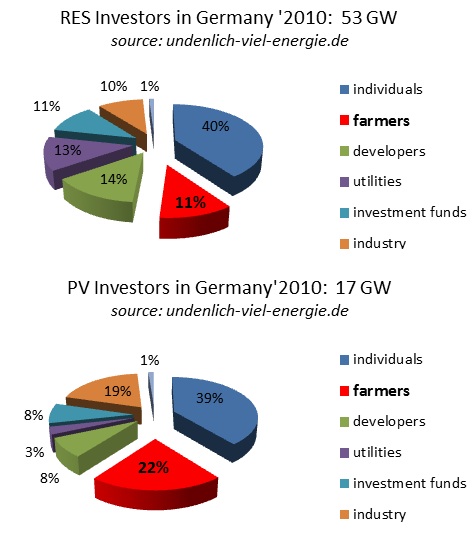

Even starker differences occur in the RES ownership structure, especially in the currently most dynamic segment – prosumer energy. In Germany already in 2010 there were some 4 million producers of electricity from RES. A majority of these had small installations (average capacity of ca. 20 kW). The figure illustrates the structure of German investors in the entire RES sector and, as an example, in photovoltaic (producing electricity from solar energy – ed.)

Overall structure of RES investors (over 4 million installations) and in photovoltaic (PV) in Germany in 20120. Source: Undenlich-viel-energie, own elaboration IEO.

As one can see, some 11 percent of all RES investors (share of the total installed capacity) are farmers, and in the photovoltaic (PV) sector, their share is as high as 22 percent. The farmers alone have invested over 14 billion euro in PV. Individuals and households are the major RES developers in Germany (ca. 40 percent share of the total capacity), while the traditional utilities have only 13 percent, and in the PV segment – a mere 3 percent of installed capacity.

Compared to the Western states, the Polish situation on small installations looks very different. In 2012 there were 1043 energy producers in the segment of fewer than 5 MW installations. As a rule, they were owned by independent developers. The share of that segment in the overall renewable energy production was, however, only at ca. 15 percent. The twenty largest RES producers all belonged to the four national energy companies and supplied over 70 percent of the entire green energy, which clearly differentiates the Polish renewable energy market from the more developed markets in other countries. In the segment of micro-installations, less than 50 kW, only a minuscule number (257) were connected to the grid.

Without prosumers there will be no revolution

Germany’s energy policy is supported by the millions of citizens producing green energy or working in the green industry. Political and regulatory blocking of RES development, especially of micro-installations, prevents the creation of a prosumer sector and this lack makes the necessary changes in the Polish energy sector difficult which leads to the petrification of its archaic structure. The absence of perspectives for the national RES market impedes the expansion of the industry producing components for renewables, because of which Poland loses a major pillar in the development of the so called “green economy”.

Poland, justly emphasizing both security and competitiveness in energy policy (though unnecessarily negating climate protection goals), in practice, without a societal, dispersed renewable energy sector, worsens its situation in both of these areas. The almost programmatic split between the Polish and the German energy policy is not good for Poland and at the same time does not help Germany in the accomplishment of the difficult, but vital breakthrough.

* Translated from Polish by Kacper Szulecki.