Fold a page in two and puncture it with a pencil – two points separated from each other by the width of the paper have thus been connected with each other in a higher dimension. This classic analogy (two dimensions of surface are used here as a model for three dimensions of space) explained to the character and viewers of Interstellar the operating principle of wormholes: tunnels linking points which can be separated from each other by any distance in space.

And this is how I would illustrate the relationship between science-fiction cinema and science-fiction literature: they are separated by a distance which is hard to overcome, their encounter and exchange of information require an extraordinary event, such as opening a tunnel in hyperspace. Although some regard SF as the mainstream of world cinema, some argue that SF cinema practically does not exist today. It all depends on the weight you attach to the science bit in the SF. Personally I am closer to the latter view.

1.

It amounts to a show-business dogma that in order to succeed, a blockbuster film must contain some fantasy (fiction) elements. For it is in them that the machinery of visual poetry composed by computer graphic artists and the painters of the adrenaline rush finds its fullest expression – and it is these two (and the stars) which attract mass audience to multiplexes. Sophisticated acting, psychological subtleties and complex storytelling are sought in cable television series (and sporadically in a three-hour Turkish or Iranian film, in the intimate art-house cinema).

In the top twenty of the most successful films in 2013 there were just a few non-fantasy films: Fast & Furious 6, (6th place), Gravity (8th), The Wolf of Wall Street (17th), The Hangover III (19th), and Now You See Me (20th). And both FF6 and Gravity rely on special effects to a much larger extent than many strictly fantasy productions; Gravity is for the most part pure computer animation.

For contrary to popular belief, Gravity is a science-fiction film only to an extent to which a thriller about a train crash or a motorway car chase can be such: they also feature exaggerated coincidences and tragedies accumulated for the purposes of the plot. Like Apollo 13, Gravity is a well-made drama with the plot set in the outer space of today or yesterday. But what matters for pop culture are superficial aesthetic associations rather than logical analyses. Even when orbital tourism becomes commonplace, for long years any movie with vacuum and stars in the background will be automatically pigeonholed as SF, even if it were a gay love story taking place on board of the Soyuz-Apollo.

But Gravity was an important film for other reasons, mainly because it was the first instance fully exploiting the 3-D technology in a 3-D environment; that is the environment of supra-planetary weightlessness, where no dimension is naturally singled out: we must choose our axis of orientation ourselves. For even underwater or atmospheric evolutions filmed in 3-D give us our bearings in relation to the horizontal plane, telling us what is up and what is down. Only Gravity allowed the viewer to feel as if he or she was really launched from two dimensions into three. And the metaphorical message of the finale, where man rises over impure nature like a god, shedding the chains of the laws of nature, may serve as a visual motto of the Second Exodus into Cosmos.

2.

But Gravity is an exception – it is not from the land of realism, but from the opposite side that various cinematic entities genetically alien to science-fiction raise its banner on their masts. For a “science-fiction” movie with the science element missing has nothing in common with the genre. The distinguishing features of the SF for generations have been the subject of heated arguments, remindful of the debates of mediaeval scholastics. For the purposes of reflection on cinema a simpler and more loose definition will suffice: in the image of the presented world, different from contemporary or historical reality, science-fiction must at least try to preserve logical coherence and correspondence with the current state of scientific knowledge. It may of course fail in these endeavours – then it is bad SF, but still SF.

When we adopt such a perspective, we will understand the position of purists arguing that SF films appear so rarely that we are hardly allowed to speak about “SF cinema” today. Neither the adventure stories for Young Adults set in fantastic scenery (and the Young Adult convention has broken away from its demographic target, it is by no means teenagers who mostly read and watch works labelled as “YA”), nor the epic fantasy spectacles , nor fairy tales from Disney and Pixar, nor the countless adaptations of comics, nor the Vampires, Transformers, Vaders, Riddicks, werewolves and zombies have the right to the name of “science fiction”.

It is also unclear how to treat films such as Lucy and Limitless, where a single hypotheses aspiring to the scientific status is drowned in a sea of comic book absurdities. If you were dealing with a book, the matter would be simple: on paper such a story would offend us as archaic and vulgar – just as we are offended today by the screen mimics of silent film actors.

But cinema has long been lagging behind science-fiction literature – by 30, 40 years. The distance is growing, the two points move away from each other, the wormhole encounters are increasingly rare.

3.

Where does this unique difficulty in translating the content from one medium to another come from? Hard SF – science fiction treating its scientific nature most seriously – walking two or three steps ahead of the increasingly faster shifting frontier of science, has gradually drifted away so far from what the so-called average recipient knows that to understand the plot of such a book and the concepts driving its world you need:

(A) a reader with a specialist education in natural sciences;

or

(B) long scientific lectures given in the book itself (so-called infodumps).

When Wells was creating his scientific fictions at the turn of the 20th century, everyone could understand the notions of travelling in time or an invasion from Mars. Half a century later the American science-fiction from the Golden Era (it was the period of the greatest optimism about the power of the human mind and the salvatory role of technological progress) remained in touch with still quite numerous groups of readers: those who occasionally paged through popular science periodicals or at least listened attentively to their physics, mathematics and biology teachers at school; for that was sufficient. And in the early 21st century science-fiction operates at the cognitive horizon of postgraduate students of cosmology, quantum physics, philosophy of mathematics, molecular biology or cognitive science.

Transmitting this kind of knowledge, fundamental for understanding the plot and the image of the word, is incomparably more difficult in a film than in a book. To tell the truth, above a certain level of accuracy it is simply impossible. To summarise several pages long infodumps in three lines of dialogue without important losses, without using words going beyond everyday language, without using numbers, to drive it into the viewer’s memory in one go (in a book you can always return to a given paragraph with an appropriate explanation, but in a movie theatre you cannot run the tape back), and all this without making the viewer’s attention drift – it is a challenge of truly titanic proportions. We would be violating the very nature of cinema. Film is a medium of emotions, aesthetic impressions, it relies on the viewer identifying with the dramatic situation of the characters, on movement of events and images. Intellectual discourses look best on paper.

But also in literature science-fiction has become a niche within a niche. It is much easier to provide people with the pleasure of escapist adventures in worlds of imagination based on magic and pure convention. And this is what 99% of what we stubbornly call science-fiction consists in: a free playing with sceneries, aesthetics and archetypes which were deposited on the popular culture of previous generations. When you read contemporary fantastic bestsellers (mostly belonging to the young adult category), it is impossible not to notice that the point of reference and a source of fascination was not science-fiction literature, but cinema and video games. Science-fiction has become the appendix of culture.

4.

In the case of the cinema there is a second key element: money. Okay, literary SF is a game for a few thousand freaks who are not just reading books, but they are also interested in the newest scientific and philosophical ideas. Meanwhile big-budget cinema has to be an entertainment targeted at consumers of tabloids and hamburgers.

And this is not an accidental feature, but one that originates from the very nature of film production. You can write a book after hours, as a hobby, at no cost; creating a film always requires money, and pictures meant for global distribution and based on innovative special effects are the most expensive – you cannot make them for thousands, but for millions of viewers.

By definition, therefore, there cannot be a SF movie based on ideas which have not yet penetrated to the popular imagination. The distance is growing. The genre’s traditions are drifting away. The subjects currently prevailing in trail-breaking SF literature – Technological Singularity, post-humanism, advanced nanotechnology, bioengineering and ecological dystopias – have not permeated pop culture yet.

The Matrix by the Wachowski brothers discovered the paradoxes of virtual reality for cinema audience thirty-some years after the publication of books by Lem and Dick describing this notion. Radical transhumanism knocked on the doors of cinema a quarter of a century after emerging in literature. The Fountain by Aronofsky, the first cinematic transhumanist fairy tale (Death is a disease. There is a cure) was released in 2006. This year Hollywood took a risk – and failed – with the big budget Transcendence featuring Johnny Depp. Lem’s Golem XIV appeared in print in 1981. Classic SF works of the previous generation – Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) and Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992) – are only now going into production. And they do not have it easy in Hollywood: there is still too much to explain to the ”average” viewer. It makes much greater sense to direct all these resources and funds on an adaptation of another comic book or a Young Adult adventure story.

As far as I know, the only successful journey of Hollywood through a wormhole leading straight to contemporary SF literature was Her by Spike Jonze. But even there the director performed quite an acrobatics with the screenplay in order to describe Technological Singularity never once using the term “Technological Singularity”. (Singularity means a point where the rules governing the process so far collapse: beyond this point the process is indescribable or gives absurd results. For example, the mathematics of classical physics collapses in the heart of black holes – and in the same way technological progress falls behind the horizon of human understanding when it is no longer human beings but machines created by them which design successive, increasingly more perfect machines).

Such cases as Kubrick’s Space Odyssey only confirm the iron rule: when SF cinema attempts to catch up with SF literature, it flops and only much later achieves the status of a cult movie and a masterpiece – when it is appreciated by future generations.

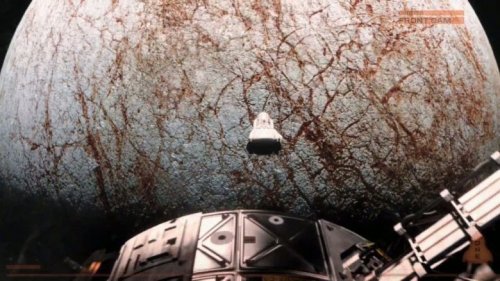

Theoretically, this gap may be filled by low-budget, independent productions. And indeed there is a number of noteworthy films trying to translate conceptual literary SF into cinematic images. Perhaps the best of them is the Primer from 2004, made “in a garage” for a handful of dollars, without any special effects. Gems from last year include OVX: Manual (ontological SF in the style of Chiang) and Europe Report (old-school outer space sci-fi). Similarly minimalist budgets were behind successive episodes of the British anthology/series Black Mirror, most resembling traditional SF stories based on an Idea. But even the best of these productions die childless, without changing mass consciousness, since they are watched by not much more people than would read analogous books.

In this sense perhaps the most effective exponent of crucial ideas of the modern SF is Jonathan Nolan, brother of Christopher Nolan, as the author of Person of Interest. This series, aired in open American television with viewership exceeding 15 million, is gradually becoming an almanac of post-cyberpunk themes in the style of late Gibson or Cryptonomicon by Stephenson. Nolan in fact tells us the story of the birth of AI leading directly to technological singularity. You can fast-forward the fights and shootouts; the tastiest concepts and games appear in the background. But since the series maintains the format of a buddy thriller and Jim Caviezel punches somebody in the teeth in every episode, mass audience is watching Person of Interest without feeling an instinctive allergy to intellectual SF.

5.

Cinema, especially Hollywood cinema as a machine for commercial draining of the subconscious of the global society, remains very sensitive to Zeitgeist changes.

It is not cinema scholars and art critics, but sociologists that are the bests reviewers of American blockbusters. For what is most interesting in these works is revealed through comparing background details: what social, cultural or legal changes occurred between the seventh and the eighth remake of the Superman or the Spiderman. Of course, the artists play with such subtleties and little details for purely commercial reasons: the better they sense the spirit of the time, the more tickets they will sell. So you can say that they are slaves of the Zeitgeist. (Every artist is, but they probably are the most conscious ones.)

Very few gain such a trust of the industry that they can throw $200 million into a film which does not follow the trends, but actively influences them, turning personal fascinations of the director and screenwriter into visual symphonies.

When Stanley Kubrick was making Space Odyssey in 1968, we were in the middle of the Apollo program, a tight space race between the USA and the USSR was going on, and astronauts and NASA scientists were the stars of pop culture. This pioneering cosmic spirit finally expired in the 1980s. This abandonment of space exploration was clearly reflected in SF literature, which focused on forecasting the development of the information society, cultural changes on Earth, redefinitions of being human and exploring the mysteries of the brain, computer, consciousness. And the outer space has become the next Neverland: a playground full of archaic visions of the past, a sandpit of favourite escapisms.

Today Zeitgeist is reversing again thanks to a co-incidence of three processes:

(A) the new economic powers of the East and South, especially China, struck out for the outer space with a fresh energy;

(B) the United States decided on a fundamental change of their space exploration strategy, shifting the funding of research and development from NASA to the private sector;

(C) political, scientific and military projects have been gradually overshadowed by purely commercial business projects: orbital tourism, telecommunications, sourcing of raw materials in space, mass entertainment (an expedition to Mars as a reality show, etc.).

I perceive both Cuaron’s Gravity and Nolans’ Interstellar as symptoms and cultural catalysts of this change. In fact, Christopher Nolan presented himself during the release as a kind of spokesman for the grassroots campaign for humanity’s return among the stars: the Second Exodus in the Cosmos. He passes the baton of scientific fascination to children of the next generation.

6.

I am happy to believe in such a loop of the imagination: having seen Kubrick’s film, the Nolan brothers are entertaining for many years the following dream: “And why couldn’t we make SUCH SF films? What a Space Odyssey we would make today!” And finally Christopher Nolan achieved such a status in Hollywood that he was able to fulfil this dream. And he did. Resemblances and cross-references between Interstellar and Space Odyssey, as well as tributes of the former for the latter, are so evident and numerous that we cannot put it down to reviewers’ over-interpretation. They begin from the very plan of the space expedition: first a slow, many years long journey within the boundaries of the Solar System, and then a leap into hyperspace. Nolan’s wormhole is located under Saturn – Kubrick’s monolith orbited around Jupiter. Kubrick’s famous trancelike sequence of the gravity tunnel is replaced here by a (shorter) ride through the wormhole. The construction of the spaceships is similar, with a ring-like module for simulating earthly gravity. Indeed, the whole design of the spaceship, machines, suits, etc., and the overall “space aesthetics ” – sharp black and white in a vacuum, no sound, framing, editing – follow the path designated by Kubrick. We also have artificial intelligences with which the characters converse during the trip; and the basic form of these robots is a spitting image of Kubrick’s monoliths. One of the key dramatic sequences of Interstellar is an attempt at crossing an open vacuum between non-sealed modules –in the Odyssey the astronaut succeeded, and here it leads to a disaster. And we also have the same theme of benevolent creatures with divine power, never speaking directly to our world, acting from beyond the frame and the story. In Interstellar they produce a five dimension construct (two dimensions of time, three dimensions of space) beyond the horizon of the black hole. The construct of Kubrick’s monoliths, created for the purposes of the astronauts’ “afterlife”, was less spectacular, but it also transcended human understanding.

These cross-references are certainly more numerous. In the era of Google there is not much point in summarising the content of the film here. In just a few seconds you can find blogs analysing Interstellar scene after scene. There are also infographics very neatly presenting its storylines and temporal paradoxes. (Today you practically do not have to watch a film in order to be able to discuss it meaningfully.)

7.

What has not been written about Interstellar yet?

All promotional materials and reviews place the plot simply in the “future”. Personally I am not certain if we are not dealing here also with alternative history. Especially that in the end everything comes down to time travel.

We know that in the world of Interstellar the Apollo programme had been launched – but apparently soon after all these climate disasters and plagues devastating food supply started, leading to a dramatic depopulation of the Earth, cultural stagnation and isolationism. (By the way, Nolan’s assumption that there is no place for the military in the times of famine, poverty and disasters, is erroneous. On the contrary: it is in such periods that the army becomes the leading force.)

The protagonist’s conversation with his daughter’s teacher, when we learn that official history has just been rewritten Orwell style and that in the new version man has never landed on the Moon and the whole Apollo programme was a very successful government mystification – can serve both as a catalyst of emotions behind the “return of humans into space” and an invitation to a more lenient way of looking at the presented world.

And what about global warming and the greenhouse effect, which, extrapolated from our world, should function as the main engine of destruction? Instead of this Nolan’s Earth is destroyed by unspecified disasters and plagues.

The extended director’s cut will probably provide us with additional materials allowing us to verify this hypothesis. And even if not – a work of art is a vessel containing more meanings than intended by the artist, it builds its own rationality.

8.

The film’s title, Interstellar, might have been translated into Polish as “Interstellar journey”. The distributor correctly did not do it, retaining the original English title, for even for casual consumers of culture such a title would sound suspiciously old-fashioned. In literature titles such as “Space Odyssey”, “Stellar expedition” and so on were acceptable in the 1950s. What Nolan transferred on the screen was not a specific SF novel, but the collective imaginary world of the 20th-century “hard outer space SF” adapted to 2014 standards.

The Nolan brothers evidently made a deliberate choice here. If you break down the film into concepts, you will get a kind of catalogue of motifs from 20th-century outer space SF. Starting from the very idea of a journey bypassing Einstein’s limit of the speed of light, through the concept of wormholes (we already have multi-volume cycles of space operas with galaxies connected by networks of wormholes), relativistic effects prolonging human life and pulling people out of the history of mankind (The Forever War by Haldeman is still waiting for a film version), various visions of colonising space, including sending human embryos to an alien planet (this is the soft version; in the radical one you send pure information about the structure of human DNA, without any organic material) up to such scenery ideas as orbital colonies established inside cylindrical centrifuges. So a sense of familiarity prevails: what we see on the screen are things well-known from books. And we perceive them as natural – thanks to the seriousness with which the director treated them.

This is no small achievement. It means that Interstellar reset the realism of the future. What Nolan transferred on the screen, was not a specific SF novel, but the collective imaginary world of the 20th-century “hard outer space SF” adapted to 2014 standards.

Ground-breaking sci-fi movies usually set a new standard for reliability of the picture of tomorrow. It was so with Kubrick’s Space Odyssey, and then with the movies made by Ridley Scott, James Cameron and others. We recognise this transition in a change of the sense of realism: from that point on futures based on old visions seem artificial, tinfoil, untrue.

This is not a trick of filmmaking, but the result of hard and time-consuming conceptual work. In the campaign promoting Interstellar it was emphasised that the artists consulted Kip Thorne, a physicist responsible for one of the versions of the theory of wormholes. He provided, for example, equations which the Nolans run through supercomputers (a Hollywood blockbuster has a big budget than departments of theoretical physics), which produced the first so rigorous visualizations of the black hole with a gas disk. In fact this is not a sensational exception, but the rule: Kubrick, Scott, Cameron, Spielberg, Nolan – to build their visions of the future they all used people, companies and institutions really forging this future, both in science and in business.

But this does not guarantee futurological accuracy – only achieving a temporarily sense of realism. Futures depicted in SF very quickly become obsolete. But although obsolete, they by no means die; they become these Neverlands of teenage escapism, lands of dreams, daydreams and games of imagination, to which the readers and viewers return with pleasure despite the passage of decades, fully aware that such futures will never arrive. This is what has become with the earthly urban future as portrayed in the classic works of cyberpunk.

But you can deliberately jump over the middle stage of this process, not even trying to make your vision of the future credible, since the very start designing a Neverland infecting mass imagination, lightly sprinkled with SF aesthetics. This is what George Lucas successfully did, creating his space fantasy called Star Wars.

The vision of space travel from Interstellar will also sooner or later become a charming anachronism. For now however, it is a standard for measuring the “truthfulness” of science fiction on the screen.

9.

In some respects, Kubrick’s Space Odyssey, made half a century ago, still seems more modern, more mature. I mean above all the methods of building the narrative. A huge difference is made here by the margin of un-literariness and poetic allegory maintained by Kubrick (although this was what he was pummelled most harshly by the first reviewers).

In literature this awareness appeared in the 1970s: namely that our present – our real rather than virtual reality – for people from past centuries is nothing, but science fiction, and yet we also speak about it in the language of allusions, metaphors, magic. So we can speak in the same way about the future, first designed under the rigours of hard SF; and this is a more “real”, fuller story than engineering narratives/reports.

This leads us to the fundamental problem with the drama of Interstellar: introducing beings whose power is in fact equal to the divine one. Whether they are aliens or people from the future, their omnipotence will capsize the logic of any story. A similar paradox undermines the sense of stories happening inside a dream or virtual reality: if anything is possible, nothing matters, nothing possesses any weight. Kubrick was able to disentangle himself from Moebius better, thanks to the poetic allegories of the finale. Meanwhile Nolan, choosing literary explanations, fell into a spiral of multiplying additional assumptions. For example, that although these are omnipotent beings and can reach to any moment in the past or the future, for some arbitrary reason they need help of a primitive human in communicating a set of digital data. But again we don’t know why this human cannot communicate this data directly, rather than employ tactics of a Victorian spirit knocking books of a shelf. Etc.

Kubrick also does not resort to banal sentimentalism. Nolan does not shrink from emotional blackmail based on the methods of Nicholas Sparks or Coelho (love is the only force that transcends time and space). This goes together with hard SF like Paris Hilton with a slide rule.

But Christopher Nolan treated us in Interstellar to a few purely cinematic innovations. Cosmic blockbusters dazzle us immoderately with spectacular images of outer space, stars, planets, space stations, etc. And although in this domain Interstellar may boast of unique specimens of a black hole and wormhole, the camera does not focus on them more than on any other element of the scenery or the environment which happens to be important for a given scene. Some cosmic panoramas even seem deliberately ignored, spectacular phenomena flash in the corner of the frame, the cameraman devotes as much attention to a landscape of an alien planet as to corn fields in Texas. The camera behaves in exactly the same way when showing the interior of the cylindrical station/colony towards the end of the film – as if we already knew a thousand of such colonies.

All these details add up to this impression of new realism: “Okay, these are stars, these are planets and this is how you fly between them, nothing special, nothing to write home about, let’s move on.”

10.

There is in Interstellar one truly subversive thought – not original in SF literature, but representing a nontrivial challenge for the mass audience – the idea of denying the self-preservation instinct and sacrificing oneself not for children or spouses, not for the family, nation, civilization or God, but for Homo sapiens as a biological species. The Nolans presented this idea when justifying one of the two variants of the colonising mission: humanity on Earth is dying and will die, the pilots will also die with their genes and memory – only frozen DNA will survive. And on the basis of it, from scratch, on a cultural blank slate, a new humanity will grow on a new planet. Old humanity will die – Homo sapiens will survive.

Let us consider the consequences of assuming such a perspective. What system of values speaks for propagating biological information on the level of the species? It is difficult to resist a comparison with our own attitude to other species of animals and plants. When a species dies out, we regard it as a damage – an evil has been done. But it is evil only in so far as it has a morally responsible perpetrator, that this man. The last dodo disappeared from the face of the earth – and we may feel guilty, for it was man who exterminated this clumsy flightless bird. But animal and plant species have died out anyway, within the natural course of history of nature. Let us imagine a force “artificially” preserving every species that comes into existence – it would demand building a completely illogical meta-ecological system with a capacity of millions of continents.

But Homo sapiens is a unique species, because it is intelligent, self-conscious. If, however, that distinguishing feature of man does not belong to the sphere of biology, but of cognition, it is culture, the world of the mind, which should be preserved and propagated. (As the godfather of contemporary nerds, Sherlock Holmes, states: “I am a brain, Watson. The rest of me is a mere appendix.”)

The return to biological, animal/racist identity of man is often interpreted in the spirit of overcoming intraspecific differences: if we think about ourselves as one clan, family, inhabitants of one house, we will stop to cut each other’s throats. And it is the first images of the Earth as seen from outer space which are supposed to have persuaded us to adopt such a perspective.

The most radical contemporary ecological movements, using the same logic, but reversing the signs of the values involved, are pushing the idea that it is necessary to erase Homo sapiens as a species, so that the rest of nature, liberated from oppression and the poisonous miasma of civilisation, could heal itself and return to the “natural state”.

The vision of “colonization through embryos” presents itself as an obvious complement to and a logical continuation of the above proposals. Man (humanity) disappears from the surface of the Earth, the tormented planet heals its wounds, regains its climatic and biological balance – and is it not the original cause of plagues and climactic disasters ruining the Earth in Nolan’s film? – while the DNA of humans blooms from zero on some other, sterile planet.

Are we capable of empathy on such a level? Should we even try to muster it?

11.

Okay, you cannot explain new scientific ideas to a film audience – but you can get it accustomed to them. When leaving the theatre I was cursing the Nolans for the absurd idea involving the planet with slowed-down time. It is orbiting closely enough to a black hole that relativistic effects in space-time bent by the whole make one hour on the surface of the planet equal to seven years on Earth. Explanations provided by the characters amount to comic book generalities: about Einstein, mass, speed of light, etc. And yet so close to the black hole tidal forces would shred any planet to pieces! Quite angry, I soon found in the net many similar charges and grudges of disappointed SF hard-core fans.

And then I discovered Kip Thorne’s book The Science of Interstellar published simultaneously with the release of the film. Thorne presents very specific conditions and various additional assumptions that he adopted for his astrophysical model, including the equations supporting particular simulations. For example, that relativistic distortion of space-time is connected in his model with a very rapid rotation of the black hole. And the astronaut survives the dive under its horizon thanks to the extraordinary massiveness of the hole, producing a large distance of its Schwarzschild sphere from the central Singularity: the gravity gradient on the body of the astronaut is not so big. Etc., etc.

This is the way that Nolans drove a wormhole between SF literature and cinema. Unable to insert scientific discourses inside the film, they exported them outside, to the traditional medium proper for them: back to the written word, back to the book.

Apparently the book is not so easy to replace. Is it possible that hard SF is a happy exception? It is impossible to jerk it out of literature without losing its conceptual essence, its rationale; at the same time it still inspires the imagination of creators of art influencing the masses, powered by a living science.

In the world of illiterates immersed in multimedia fictions the producers of these fictions will at least read today’s Wellses and Lems.

12.

But even though at odds with the physics of the black hole, I was watching Interstellar with genuine pleasure. A big-budget SF film which an adult viewer can watch without an impression that the director and screenwriter regard him as a moron or a twelve year old with ADHD is such an amazing rarity that for a long time we will be using it as a counterexample to standard Hollywood fare.

Also difficult to overestimate is the creative and aesthetic consistency of the Nolans. A technology and astronomy buff woke up in me again. I was keenly following particular engineering solutions (for example, the seemingly clumsy robots inspired by Clarke’s and Kubrick’s monoliths turned out to be surprisingly versatile designs.) And I can never get enough of panoramas of deep cosmos on an IMAX screen.

The figure of Abed in the Community reached such a concentration of nerdness that it seems closer to posthuman artificial intelligence.

In the Interstellar there is a number of small details which are meaningful only for connoisseurs of SF and which also betray a profound kinship of their fascinations, reading matter and mentality with the Nolans. Hungry for true science-fiction in the cinema, I good used to making do with the substitutes, collecting the seeds of SF sown in the least expected cinematic genres and formats. And the last decade has seen a real invasion of disguised nerdism on Hollywood. An increasing number of these tropes, themes, fingerprints of SF mentality appears in contemporary productions of the Dream Factory.

First of all, in almost all procedurals (series and feature films about policemen, doctors, lawyers) the dominant figure of at least the second plane is now a cerebrate with an Asperger syndrome, often planted on the borderline of autism and/or superhuman genius. Within two generations a complete reversal of the poles of appeal has occurred: then “nerd” was a synonym for “loser”; now “nerd” is Dr. House, Sherlock Holmes, Sheldon Cooper, Spencer Reid, and Walter White. This type of protagonist and this way of seeing the world has sunk in popular culture so deeply that it is no longer just a backdrop, but the main axis of hit sitcoms like The Big Bang Theory or Community. The figure of Abed in the Community reached such a concentration of nerdness that it seems closer to posthumanist artificial intelligence. And the content of procedurals themselves is increasingly tilting towards science and technology. A sign of the times is the huge popularity of TV police dramas entirely devoted to laboratory analysis of scene of crime traces (CSI with uncountable spin-offs and copies), or equally strict behavioural analysis of criminals (Criminal Minds and their progeny). It has become a standard to match two main characters on the basis of the principle male/female, nerd/non-nerd; and the nerd does not need to be a man (see Bones). It is not just a question of superficial “simulation of the scientific”; it is assumed here that the mass audience understands not only the general method of scientific reasoning, but also the rich subculture of natural scientists. The humour in The Big Bang Theory is based on references to such seemingly niche productions as Battlestar Galactica and Firefly – and yet it is currently the most popular sitcom in America.

In the subplots and the background this has penetrated to almost all formats, genres and conventions. The Good Wife, seemingly as remote from SF as possible, one season ago climbed to the level of technological paranoia worthy of Person of Interest. Classic SF motifs – time travel, alternative words, transfers of consciousness – no longer surprise anyone even as foundations of Harlequin love stories (the series Outlander is the newest example of that). Last year television nerdism entered the phase of mature classicism: we saw the appearance of productions successfully dramatising the very sociological and historical phenomenon of nerdism (Silicon Valley, Catch Haltand Fire).

Unable – for the objective reasons described above – to shoot full-blooded science fiction, filmmakers seem to season their works with crumbs of baits which are like a code of some secret brotherhood. Matthew McConaughey uttered the best SF monologue of this year – by no means in Interstellar, but in the HBO criminal series True Detective; it was a lecture on the theory of the multiverse, n-dimensional Brans and such like. (A TV series can withstand infodumps, for which there is no time in a feature film). In another episode the same character makes a long digression about religion as a memetic virus.

Few people now write and read hard SF, but in some mysterious way it still moves between minds like this virus. If a statistical analysis was made how many old SF fans – not fans of comic books or fantasy, but hard SF – are there among top Hollywood directors, I bet that the study would result in an disproportionately high percentage of such artists.

Where has this phenomenon come from? Here we are entering the dark underground of culture, the metaphysics of fiction. Attractiveness of artistic creation is to a growing extent relying on the power of pure immersion in fiction, in its entire world (reality). And there are two conventions which shape the minds of engineers of immersion: historical fictions (where, however, the world is a given) and fantastic fictions (where you have to construct the fictional world yourself – and the “harder” the SF is, the more rigorous you have to be). The same obsessive totality of artistic creation is responsible for the success of the drama series Mad Men and the comic book blockbusters from the Marvel studio.

This is my favourite conspiracy theory: it is not the Jews, but science fiction fans that the rule in Hollywood.

Film:

“Interstellar”, directed by Christopher Nolan, USA, United Kingdom, 2014