Tomasz Sawczuk: In the past 26 years, since it reclaimed its independence, Poland has not been affected by problems associated with migration all that much. How is this possible, since elsewhere in Europe such problems are commonplace?

Aleksander Smolar: The influence of migration and demographics on the process of Poland’s political transformations is an interesting topic, if rarely tackled. Let us focus on two moments in recent history: the changes which took place after 1989, along with – as discussed by Kazimerz Wyka in “Gospodarce wyłączonej”, and more recently by Andrzej Leder – the War and post-War period, a time when Jews vanished from Poland’s socio-economic structures, while the middle classes saw an influx from those of lower standing. The elimination of the Jewish part of Poland’s population, as well as the deportation and mass exodus of its German counterpart, had a key influence not only on the history of communist Poland, but also on more recent events.

TS: Could you describe this in more detail?

Poland’s homogeneity – ethnic, national, cultural, religious – made the transformation process much easier. It meant there were none of the conflicts which occurred in other countries and exhausted a large portion of their political energies, blocking necessary changes. A prime example of a country which, in exiting communism, descended into horrific domestic conflict is Yugoslavia, which was much more advanced at that point, far more westernized and economically connected to the West than Poland.

Of course, the homogenization of Poland is a result of the deaths of millions, and the forced migration of millions more. This is on top of other, unimaginable tragedies which have left a faint, yet potent mark on the collective consciousness. Our country has certainly been culturally impoverished; this is manifested today through a growing nostalgia for Poland of recent times, a country which is gone for good. Yet, when it comes to the socio-economic transformation which occurred over the past quarter century, this homogenization has been a singularly positive aspect, though often passed over in analysis by economists.

TS: Was this really beneficial for the process of transformation, even from an economic and cultural perspective?

In cultural terms, homogenization relating to nationality, religion and culture certainly led to Poland becoming more provincial, less creative, though this is a separate topic. Historians have often formulated the notion of serious economic downturns, the weakening of the development of Spain and Portugal was linked to the expulsion of Jews towards the end of the 15th century. The Jewish community played a substantial economic role in said countries, especially in involving them in the international system of trade and finance. The Second World War was also key for Poland, in numerous ways, along with the economic mechanisms of communism, in its turning away from the world. Although, of course, other aspects of life under communism – education, the egalitarization of the populace, urbanization – suited long term modernization, although often in pathological ways.

Meanwhile, considering the transformation taking place in Poland after 1989, of key importance was its strong sense of unity and readiness to pay a high price for the changes – for patriotic reasons: for this is “ours”, for we want to “go West”, for we all want to turn away from Russia. Hence, in a word, there were no ethnic or religious conflicts which could have pushed the socio-economic problems to the background, as happened in neighboring Ukraine.

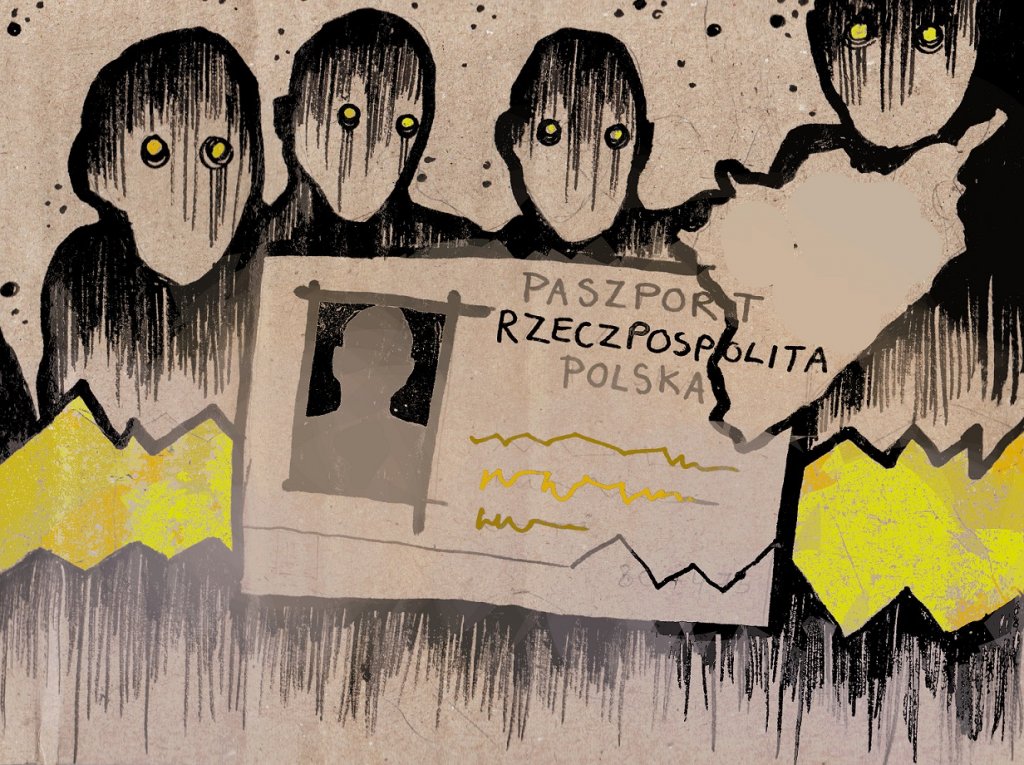

Łukasz Pawłowski: Currently, this uniformity is fading away. Poland is beginning to receive more and more immigrants.

This small stream of migration from surrounding countries – Belarus, Ukraine and Russia – is almost invisible, because the cultural differences between us are small, hence these migrants adapt more quickly. Additionally, they often don’t settle in Poland, but work seasonally and return home, or send money via their families.

Today, however, we may be facing a serious problem, for the first time ever, related to the crises in the Mediterranean Sea involving the deaths of hundreds of immigrants trying to cross over to Europe. It is hard to ignore a tragedy on this scale and something must be done – no one, however, knows what that something should be, for even if we accept all these refugees in, we know another 200 thousand are awaiting on the shores of Libya, Algeria and Turkey, in order to follow the same route. Altogether, we are talking about an estimated million displaced persons. Is Europe capable of absorbing such a vast number of new residents, while simultaneously maintaining its democratic institutions? And all this at a time of deep economic crisis, the signs of which are clear for all to see; at a time of mass organised movements aimed against immigrants and Europe itself?

TS: What is the role of Poland in all these processes?

Poland and other countries in the region are being pressured to take in more migrants. If we want external help with regards to Ukraine or Russia, we have to show solidarity relating to the South of Europe, whose problems are affecting the whole continent. This is without yet considering the human dimension of this tragedy. The problem is that, culturally and socially speaking, Poland is completely unprepared for these challenges – both in terms of public opinion and state infrastructure.

TS: Meanwhile, Europe is dominated by rhetoric regarding the tightening of borders…

But how to achieve this, considering refugees are willing to die to reach our shores? They are fleeing countries which are falling apart, places wrecked by war and famine. They want to feed their families, dreaming of a European Arcadia. There are, of course, ideas being put forth about a solution involving the wrecking all those various ships, boats or rafts on the shores of Africa, long before they get anywhere near Greece, Italy or Spain. But this is in no way a lasting solution, because all migration routes which are blocked are instantly replaced by new ones. And I’m not even talking about how cynical such a solution would be.

ŁP: Have we acted differently in the past?

European politics, with regards to illegal migration, has always been rather cynical, based on the whole on agreements made with authoritarian rulers of various countries. They were given military and economic assistance, in exchange for the maintaining of peace with regards to exiles. Today, there is no one left to keep that artificial peace. We have destroyed the Qaddafi regime in Libya, the Iraqi dictatorship, the powerful regime in Syria – all of whom were in a silent agreement with Europe about controlling migration our of Arab states and out of Africa.

TS: Should European states take in some part the responsibility for people fleeing African and Middle Eastern states?

What is meant by “responsibility”? We are dealing here with the weakness of intellectuals who, when confronted with real political matters, fail to make serious choices. This is not just a question of honorable intentions and value systems we hold up as relevant. We must also consider that European states are democratic entities, where rulers are chosen by popular vote. And the people can simply remove legitimacy from those same rulers, should they agree to take in a mass influx of migrants. We can see this in the example of France, where the popularity of Marine Le Pen and her National Front is growing. In actual fact, she has taken over the discourse from the Left and the liberals, as well as republican sides of the debate. We are now hearing about secular traditions, and the defense of the secular state, when not that long ago the National Front was closely aligned with the most conservative elements within the Catholic church. Meanwhile, criticisms aired by the Front are appealing to an increasing number of people in France, especially those from lower class backgrounds, who often live in the same areas as the newly arrived migrants.

In many countries, the increasing presence of anti-immigrant moods doesn’t come out of racist leanings, but from a reaction to a large proportion of the new arrivals challenging fundamentally liberal values.

TS: In France, do Muslims – even second or third generation – really question European values?

This is a very interesting phenomenon. The first generation of immigrants, mainly from Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, was absolutely satisfied with being allowed into France, as well as allowed to work. They accepted everything the Republic offered, and which is being attacked today. This was the time when special areas were selected on the outskirts of towns for the building of cheap housing estates for new arrivals. The aim was to create decent conditions in which people could live, yet the unintended outcome was the creation of ghettos.

This is only one of the problems France is faced with today, concerning the second and third generation of migrants. We are here talking about people who were born in France and are French citizens, yet who speak poor French and do not feel in any meaningful way connected to their country. There has been no real integration with the indigenous population, something which causes feelings of exclusion and frustration. This leads to the rejection of France by a part of its own population. I remember, many years ago, the shock experienced by the French during a football match between Algeria and France. The gathered crowds cheered mostly for the Algerian team, with the Marseillaise was booed at.

ŁP: The same thing happened during a Germany-Turkey match. What is even more surprising, many of those choosing sides against Germany or France have never even visited the homelands of their parents or grandparents. How much of this loyalty is then down to a longing for places of the past, and how much simply a gesture of protest?

We aren’t really dealing here with any sentiment for countries of origin. The young generation born of immigrants from Islamic states – for it is they were are mostly concerned with here – construct their identities around several elements. Firstly, the rejection of the state in which one resides. Secondly, religion. The first generation of the newly arrived moved away from Islam, while their offspring seem attracted to it. It is often forgotten that Islamic states of the 1950s all the way to the 1980s, with the exception of Saudi Arabia, saw a widespread process of secularization. The main champion of this form of secular, socialist nationalism was the Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, who literally laughed at religion. The Muslim Brotherhood was outlawed. These were very different times for Arabic states. Today, we won’t find a single secular political party, while back then they were all secularized!

It was only the children and grandchildren of the first wave of migration who learnt about Islam. And the simplest form of religion is its radical form, for example Wahhabism, which emerges out of Saudi Arabia, meaning Salafism.

The third aspect which is key to the forming of immigrant identities is the sense of unity with the suffering of the Palestinian nation. The Old Continent is once again seeing a resurgence of antisemitism, but not among people of European origin, but among Muslim immigrants, who have entered into solidarity with the remains of a marginal, antisemitic Right and – as a new development – with a radical Left. Israelis and those siding with them, Jews residing all over the world, have taken on the role of “white men” lording over a scrap of Arab land, the modern embodiment of neo-imperialist, colonial West.

Adam Puchejda: Is the current situation – and I am here referring to the fortunes of immigrants trying to get across from Africa to Europe, such as those from Syria – not caused by a lack of any sort of long-term international political strategy within the EU?

Can we at all talk about the EU’s international political strategy? It’s obvious that Europe must become involved in solving the crisis of mass migration, without being able to count on help from the United States. Paradoxically, this internal crisis, along with external threats, could push the EU towards greater integration and the development of a joint foreign policy. Of course, this will be a fragmentary politic, piecemeal, but it will appear, as it is highly necessary.

The model we have been using thus far, according to which one or two of the most powerful states adapt different strategies, without asking the EU’s opinion or ignoring its instructions, is in the long term unsustainable. This is a sliver of optimism which we can extract from this whole tale.

ŁP: In this context, what do you think of the quotas on migrants being taken in proposed by the European Commission? Is there any way in which the matter of refugees could become the subject of real discussion within Europe?

I can’t see any other way, seeing as on the other side of that sea there are hundreds of thousands of displaced persons… The crises around Europe are multiplying – in Libya, Syria, Iraq – creating pressure points we cannot ignore. The problem of refugees will be far more serious than the crisis in Greece, because it is about democracy and the value systems which are at the heart of Europe itself. Michel Rocard, the French prime minister between 1988-91, said that France cannot see as its mission the saving of the whole world from misery. No single state can take upon itself such a mission. This is true, but what are the limits of our powers and our engagement?

Jarosław Kuisz: What then is the answer? The American philosopher, Martha Nussbaum, in her discussion with Liberal Culture, suggested the idea of mutual adaptation…

Her proposal is based on an idealized American model, completely unsuited to European traditions and circumstances. Europe is made up of ancient nations, which are in no way interested in adapting, the opposite in fact – what they want is for the new arrivals to adapt. Even if they are able to take in a certain number of migrants, as a generous gesture, and at a time when there are a few extra places to work and live, this has to happen under strict conditions.

The symmetry put forward by Nussbaum, apart from the fact that it is utterly abstract, also gives birth to the question: what are European states meant to adapt to? Sharia law?

International research conducted by Ronald Inglehart into value systems show that the key differences between Islamic and Western states are related to women’s rights. Nussbaum merely makes reference to the wearing of the burqa – which France has, idiotically, forbidden in public places, because this is easiest – but we are of course dealing with fundamental disputes over the rights of women and their role in public life.

Nussbaum also fails to take into account individual aspects of local European states. In French culture, the wearing of a veil can be contextualized, but one has to know a little about its history and the fight for secularization which took paces in the 19th century with the Catholic church. Without this knowledge, it appears that the banning of religious symbols is addressed mainly at followers of Islam.

JK: Do you then think that, in order to preserve the old democracies of European states, we must in the main close our borders? Should we invest in improved technologies to patrol these borders, increase the Frontex budgets and look for ways of allowing in the greatest possible numbers of newcomers, on the condition that they will assimilate?

Mass influx is not possible, because it will blow Europe apart. If we are generous enough to commit harakiri on the altar of noble ideas, let’s do it. I can’t, however, see anyone willing to commit such suicide in Europe, except for a few intellectuals locked in their ivory towers. On the other hand, the attitude of complete containment, as proposed by the French thinker Alain Finkielkraut (who was once a radical Leftist) is hysterical and nonsensical. We must look for a compromise.

JK: He says that immigrants must assimilate, and that’s that.

This must in some way be a two-way process, but not in the American sense, not when symmetry is unattainable. The Syrian political expert Bassam Tibi talked about this in your discussion with Karolina Wigura. Having been a victim of discrimination in Germany, he is a realist. Immigrants must accept certain fundamental European values: the rule of law, democracy, the role of women, the rules of equality. Hence, we have to both impose citizenship training as well as giving them the facility to advance themselves.

France, in this case, happens to be a country riddled with hypocrisy. In the French language, there is no difference between notions of nationality and citizenship. As well as being Polish, I have French citizenship and when I sometimes refer to my French friends “you”, they get very annoyed and remind me that I too am a Frenchman. But if, in my place, they had to deal with someone who was Black or Arabic, I’m not sure that this distinction would function in the same way.

ŁP: How can we prepare Poland for what is coming?

It is hard for me to formulate an abstract answer, when we often don’t even know what the questions are. Poland is a country without a colonial, imperial past, and hence it has little experience of the “Other”. A Jew, before the War, was such an “Other”, and yet he had lived on Polish lands for hundreds of years!

For societies with colonial histories, traditionally open to the world, it is given that their streets will be multicultural, that accents vary, that there is widespread tolerance for diversity at a fundamental level. I am afraid that for Poland even this small step towards adaptation will be a dramatic struggle.

*The above interview is a shortened transcript of a conversation which took place as part of a seminar in the academic cycle titled “#YOLO. The lost future of Polish freedom?” organised by Liberal Culture and the Róża Luxembourg Foundation.