In a discussion with a Romanian director, Cristi Puiu you described once the mechanism of filmmaking “as getting into the space” – first you need to purify yourself and then open to a kind of new experience. I wonder how this method worked in the case of Maidan? What does a filmmaker need to do, in order to grasp such a great, vibrant space, with so many interactions?

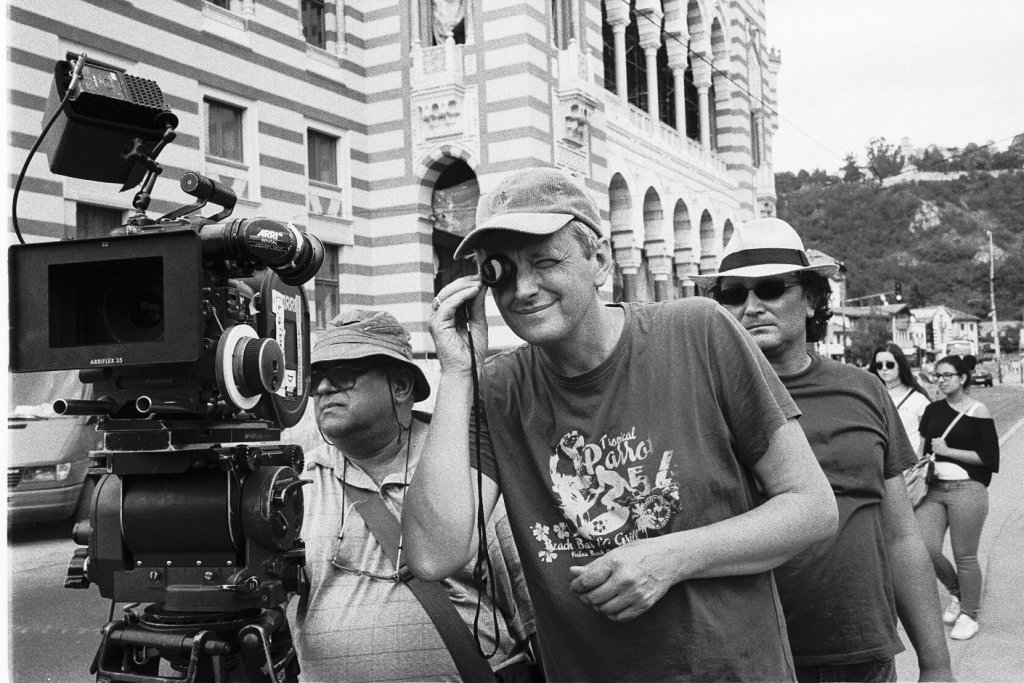

You have to be a very careful observer, like a person whom nobody sees. It means that I do not have any contact with the world around me. It is very simple. For example I shot one film, “The Landscape” where a lot of people stood waiting for a bus in the landscape. You can imagine that as we shot this film, we stood – four people – with a huge camera and a tripod, 1,5 meter in front of the crowd. In this situation everybody in the crowd has to react and will react to you. And how to avoid this reaction? There is a very simple method: don’t look into the eyes of the people.

Was it easy to apply this method in the Maidan?

No, as a film director I have many different methods how to be invisible. But it is difficult. I can explain how the film is constructed, how the camera is working, these kinds of things from a mathematical point of view, but it is difficult to explain your bodily experience. How to find the words to say: why you feel you need to be in this place, in that moment and push the button? You need to feel it and predict what will happen in next few seconds.

However being in Maidan while maintaining the disengaged position must have been very difficult. The square was calling for participation – contribution in the collective effervescence, this moment of emotional upheaval that had some aim of social change. Did you not feel urged to participate in Maidan?

I feel everything, but this is a profession, you have to cut off this feeling. Sometimes a person is like many persons inside. One person inside me feels it, another person acts, and these are separate people.

So any kind of involvement comes with a big cost for the filmmaker?

In my opinion – yes. I think in general that we can’t see real processes or real things, which surround us, because our sensibility lies to us and even our brain lies to us. You know all these magic pictures, when you think: this is this thing, but it is something opposite. Like with a face standing out from the background, and you think it is a convex face, but it is actually concave. These kinds of examples follow us during our life, so we have to be very careful. And now, with new possibilities given to us by media, it is very easy to fool ourselves, to make a face. Now, for example, take the Russian media – who built a world that completely does not exist.

What does the filmmaker need to remember in order not to get into this foolish conviction of grasping reality, while he does not manage to do it in the end? Is it about achieving the art of pure observation?

For me the most important point is that I am not only the person who wants to understand it. I want to make a film and give this possibility to the spectator. To make a film and to understand is two different things.

If I compare the scene of fighting between people with something more boring to replace it, I would prefer to remove the fighting.

At the moment I use this kind of method where I try to make shots longer and without a comment. Comment in this case is a composition, with decision of how close or how far to be. Comment is sound and editing as well. I would like to have no additional comment in episodes, and this is a way that works at the moment. Maybe in the future however somebody will use another method of propaganda, which will involve this kind of method of telling the story. But when I am making the film, the main idea is that I am trying to leave the space for spectator, to make his own decision. If you see other films about Maidan, you immediately understand from many of them, which side the director is on.

Even those made by Babylon 13, a film group posting regularly short, often shocking, documentaries of the conflict in Ukraine into their youtube account?

Like Babylon 13, which I think is a big mistake. Why should I see the film because somebody decide in my place what is right what is wrong?

Your method seems to resemble the auteur approach of Kazimierz Karabasz, who tried to differentiate himself from the communist propaganda language by purifying the art of observation, which he called the method of the “patient eye.”

Yes, I know him. But the second thing is: it is not only about observation from a distance. The question is: what do you choose for observation? I prefer to choose the very boring things. If I compare the scene of fighting between people with something more boring to replace it, I prefer to remove the fighting. During Majdan there were many episodes with blood, killing people, there was one man without a head, can you imagine?

I prefer to cut out everything that can touch our sensibility, because we are in a paradox situation. Through our sensibility media news open the door: we immediately start to empathize with the victims, because we are human. In this moment the media catch us. It is like in a TV series – they move us without our will through the story which they completely construct. There exists only one method of protection from that – to know every shot and not to allow yourself to feel compassion with it. When you watch the news for example, be like a stone.

Does this method not imply however some cost in terms of the relation with the characters? In “Maidan” there is no focus on the individual stories of any people involved in the protests. In “The Square” – a documentary by Jehane Noujaim i Karim Amer, about Tahrir protests (which was nominated for an Oscars this year), the story was built through following few main characters.

Choosing a character is a simpler method than when you have no hero in the film: to find sympathetic people, explore their sympathy and play with them a game, using them as your eyes. I did not make any documentary film where there were any characters, because I think that when you shoot somebody, you also are in the situation when somebody uses you and starts to play somebody else, the person.

Krzysztof Kieślowski once explained his decision to move from documentary into fiction using ethical terms. He said that in fiction-making the contract with the character is clear, and as a director he can invade the intimacy without feeling guilty for it.

This is true, because you are a part of somebody’s life with your film. With fiction it is a game, you can do what you want. You can kill people in the film, because everybody knows it was made. And this way, using the “lie” – or “the “fake” – you can build a truth. But with a documentary it is much more difficult. Normally 95% of the directors in documentary cinema who make a film, present it and say: here we witnessed things that happened. Which is absolutely funny, because they witnessed the things they can see in that place and that moment. This is a lie.

But what was directing the real Maidan then? What was the mechanism making this collective body, these masses move? On the basis of the movie, one can wonder whether it was a nationalistic emotion, as they start with singing anthem. Or maybe it was a religious impulse, which people there seem to be very emotional about? Or was it rather a pure rhythm, because the sound of drums, the rhythm of the space is so powerful on the screen, that you can feel like a part of it. What was directing this movement, despite the fact that it seemed leaderless – what was behind it?

In real life it was the will of all the people. When you meet the people who want the same thing, you add your will. Forget about the nationalism. This is why I say we need to redefine many words, because apart from a propaganda definition, we do not have a definition that would help us understand what happened in Ukraine. If people sing their national anthem, it does not mean they are nationalists. People respect it, as well as the flag, and who says they are nationalists?

If this is not one of the words that addresses it – what was the movement triggered by?

It is very simple. The answer is in the first days of Maidan, and in what happened before: people came to the streets and the police beat the students during the night. In Moscow it is possible – it is a normal picture, that the police beat people – old, young, does not mater. In Kiev it was never a normal picture! It is a city where people have their dignity. We asked a very simple question, and they did not listen to us: “Who made this order? And why are these people still out running free?” You know how the story ends – in revolution!

Do you think that the experience of Maidan is useful and would influence your fiction-making?

During this autumn and winter and even before I was preparing a film named “Babi Jar”. I would also like to make a film without main hero, or main heroes. However with a lot of people, extras. It is a film about the beginning of WWII, the aggression of Germans towards the Soviet Union in 1941. The main event is a big execution in Kiev, where they killed 35 000 Jews. I want to make a film about this sickness named war, this infection that exploded and how this infection moved. For that I don’t need a hero, as it will constrain me.

I prepared this film, and the structure of Maidan is very similar to what I want to make. I want to recreate the “documentary reality” – I want to make a kind of archive in a feature way, when you come and see and say: ‘ok, where did you find this material?’ With long takes, but the style is very close to the documentary style, imitates it. What is important for me is the movement of extras. If you for example know very well the world cinema, not many film directors can work with extras and really use it. I can only remind one director, who worked with extras fantastically – Pier Paolo Pasolini. It is a very difficult task if you have like 500 people, you have to pay for all of them, to achieve this kind of movement which has a reason, and that you trust. It is such an interesting task, because when you watch the film shortly, you trust not in the first plane – like main actors, and something in between them – but you have to trust the second plane. I found something like an exercise, and preparation for this second plane now for my big film in Maidan.

This explains your opening sequence in “In the fog”, a few minute-long shot presenting the groups of extras watching the execution, but not showing the faces of its main protagonists?

Of course. It is very difficult to achieve. I want to make the next film with only these kinds of sequences, because war is not a relation between some people. War is a relation between masses of people and I have not seen a film that showed us war like that – not as a drama of certain individuals, but a tragedy of nations.